Geez - What's next?

/As if there hasn’t been sufficient challenges to the real estate and home-building industries recently the current inflationary pressures plus interest rate hikes have made building an even tougher challenge.

This is a shame as increasing our supply of homes is a large factor in improving affordability. All levels of government indicate they would like to double the rate of homes being built.

They are able to influence many things in order to do their part to increase the building rate. See this blog about that :

http://www.funktionaldesign.ca/blog/2019/1/3/why-is-housing-so-d-expensive-

Other aspects affecting Canada’s ability to increase the building rate that require further consideration.

Supply of Trades:

It’s not news to indicate that our population is aging. Nor is it news that many young people are not considering vocational or building trades for careers. The bottom-line of that is not only is there an insufficient supply of the correct technicians and trades to increase home-building production, it seems likely it is not even sufficient to sustain the current rate. Certainly incentivizing persons to adopt those careers and offering more vocational training can be done but its not a quick option. This parks the problem squarely on Federal Immigration policies to increase the supply of needed trained personnel quickly.

See a recent article from the Globe and Mail discussing this issue:

Are we just getting in our own way?:

This is just one example of what I am referring to. The article discusses the disadvantages of maintaining older homes, often located in areas or properties that could accommodate greater density and suffering the sort of age-related safety, comfort and efficiency problems that modern construction would solve easily.

Other impediments, all perhaps with merit and good intentions, but impediments nonetheless, are as follows :

Tree canopy regulations.

Complete or season-related restrictions on development or site work to protect native animals.

Mandated public consultations and/or development hold-ups due to neighbour protests.

Municipal planning rules and zoning regulations that impose expensive planning processes and restrictive uses / occupancies.

Building Code regulations that go too far…or not far enough.

Am I advocating a regulation-less free-for-all? Of course not.

However, I believe some simple changes could remove time, cost and impractical barriers.

A) Instead of property owners going through a time-consuming and expensive process to hire an Arborist and/or Environmentalist to study and create a report specific to a single property or development proposal, a municipality can have their Forest Services division and Environment Protection division impose practical prescriptive solutions that cover the majority of situations (80%?). Municipalities that are not large enough to have such expertise of their own can use the standards and solutions arrived at by geographically similar municipalities or Conservation Authorities that do.

It’s naive to imagine that this will work to reduce red tape and speed up all developments but if it manages to reduce the intensive study down to 20% of the proposals, then the approach could be effective.

B) Governments are organizations that, by their very nature, are conservative. So adjusting their own long-held rules and regulations quickly to adapt to a crisis or speedily changing situation is difficult. But Incremental zoning revisions could spur some real change.

A personal example. I am fortunate enough to live in the Alta Vista neighbourhood of Ottawa after having owned and lived in a triplex in Sandy Hill and then a 1200 sq.ft. 2-storey single family home on a 30’x85’ lot in Old Ottawa South (both of which are “downtown” neighbourhoods. Our current 1.5 storey (2nd storey tucked into roof) has a building area (footprint) of 1605 sq.ft and total gross area (space above grade) of 2385 sq.ft on an irregular shaped lot (generally 75’W and 140’L) that is 10,150 sq.ft. in area. This is a single family home on a large lot 5km from City Hall (by street! - even less as the crow flies). When we moved in I remember saying to my family; “Enjoy this - there will never be a central neighbourhood like this allowed to be built again”.

Despite the fact that it changes the very type of neighbourhood I live in, I think zoning rules should adjust. But rather than eliminate R1 zoning entirely, perhaps amending regulations so that they allow quick adjustments as the City itself grows and changes would be more appropriate. For instance as transit or retail areas / community services grows, R-1 zones could shrink away from them. This may allow more speedy zoning changes to spur development in areas where intensification is desirable / practical and no need to wait for the next Official Plan to be issued.

In Ontario, the recent enactment of Bill 23, the “More Homes Built Faster Act” attempts to address many of the above development restrictions. There is the danger that Bill 23 causes municipalities to lose control of planning and sprawl occurs and/or they lose the ability to charge fees that maintain municipal services.

Having said that, I’m of the mind that local zoning regulations can mitigate that concern and I believe that it is indisputable that there is no way to double the present building rate without some sort of action to change the status quo.

Another change of approach possible at the municipal level would be to allow more mixed-use. Its a far-flung example but the following is an article that discusses the vibrancy phenomenon that could result.

I’m pretty sure that nobody would dispute that more dense, varied but vibrant neighbourhoods such as Queens Street or Kensington in TO, Jean Talon Market Area in Montreal, or Westboro in Ottawa would be a good thing. Note also that this article touches upon possible innovative ways to finance development (land swaps) and the impact of allowing simple building technologies. That’s a good segue to my next point.

Building Technology.

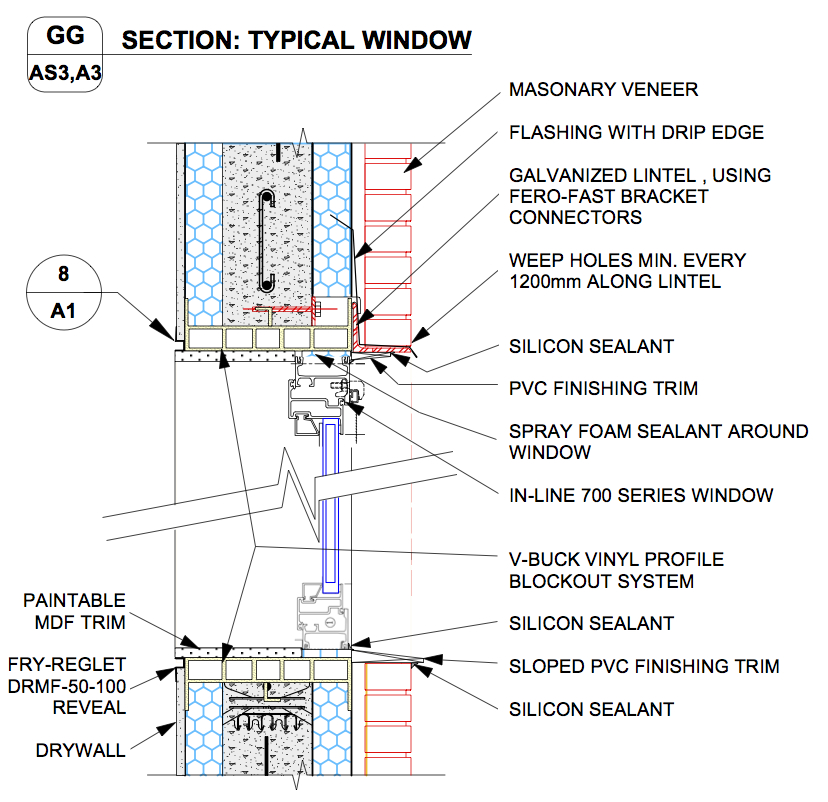

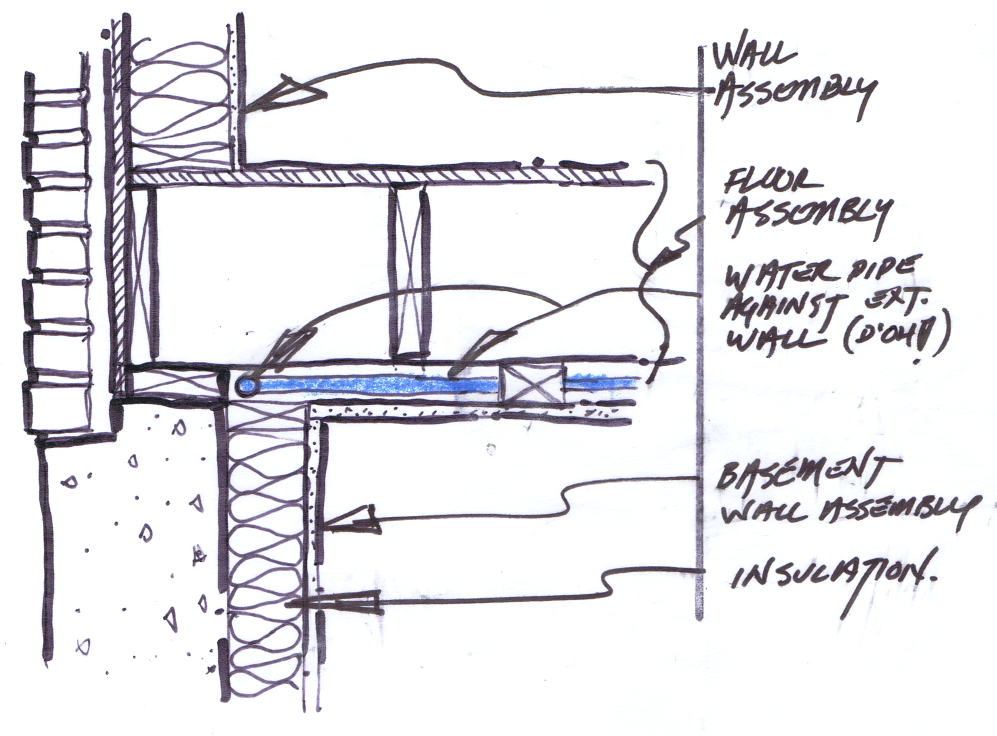

Today’s Ontario Building Code (OBC) ensures homes are safe and built to a standard that is reasonably efficient to heat/cool and durable. However because its regulations are largely built around the 150 year old practice of on-site lumber-frame construction it has limitations.

The prescriptive structural solutions within the OBC, which the use of is the least expensive method to design/certify a building, does not include TJI joists or open-web truss joists or roof trusses. These have all become very common in the last two decades and are usually a better practical and environmental choice. In order to qualify for Permit, these elements have to be specified separately by the supplier of these trusses or by an independent Engineer. This complicates and lengthens the time/ effort/ expense required to design/ certify/ Permit the building. I have been advocating to the Ministry of Housing (the authors of the OBC) that these building materials could be built to a certified standard and then its use in straightforward situations could be specified prescriptively in the OBC. That would lower the cost and increase the speed at which buildings could be designed / permitted.

A reverse limitation is that the OBC, being so closely related to typical lumber-frame construction not only doesn’t promote the use of new or different construction methods it can inhibit them. Using Factory-fabricated wall panels, Structural Insulated Panels, Light structural steel, Rammed earth walls, Hempcrete are all underutilized construction methods in Ontario. Partly because these alternate methods are i) difficult to obtain building permits for, and ii) are inscrutable to Inspectors who have little or no experience overseeing them. Not related to the OBC but also a large part of the problem is difficulty is finding builders willing to construct with these methods. Some of the above construction methods addresses today’s modern needs for tighter more efficient buildings in order to achieve low or net-zero energy use plus lower or CO2 emission standards and carbon-capture. Promoting these alternate building methods, through the OBC or by other incentives / information programs could assist.

Supply of Materials:

Manufacturing slowdowns, supply chain disruptions, and high demand has made timelines longer and added costs to the standard materials that have long been part of the building industry. Spreading the building around to other methods could allow innovation and improved buildings but could also take the pressure off the supplies/trades for typical builds and as a result, increase overall quantity of homes built.

Environmental Concerns:

Building methods that address modern issues such as climate change should also address the greater occurrence of harsher weather and climate disasters.

It feeds into this topic of affordability in two ways. Homes built to a standard that addresses the low emissions that our country has committed to achieving but not yet created building programs/ incentives to address means less expensive rework required later, when energy prices or government programs do exist.

And, more structurally resilient buildings means less time/effort rebuilding when weather event damages do occur. The following is a recent article that discusses this issue.

I am encouraged that there has been more conversation and action to address what is a real and growing problem. The solution of increasing how quickly we can build touches many public and private organizations and industries. I’m hopeful that if all of various players make a few changes it can have an affect and we get positive results. More supply of quality homes, and decreased prices so my children can afford to buy a home when its their turn !

Happy designing and Happy building !